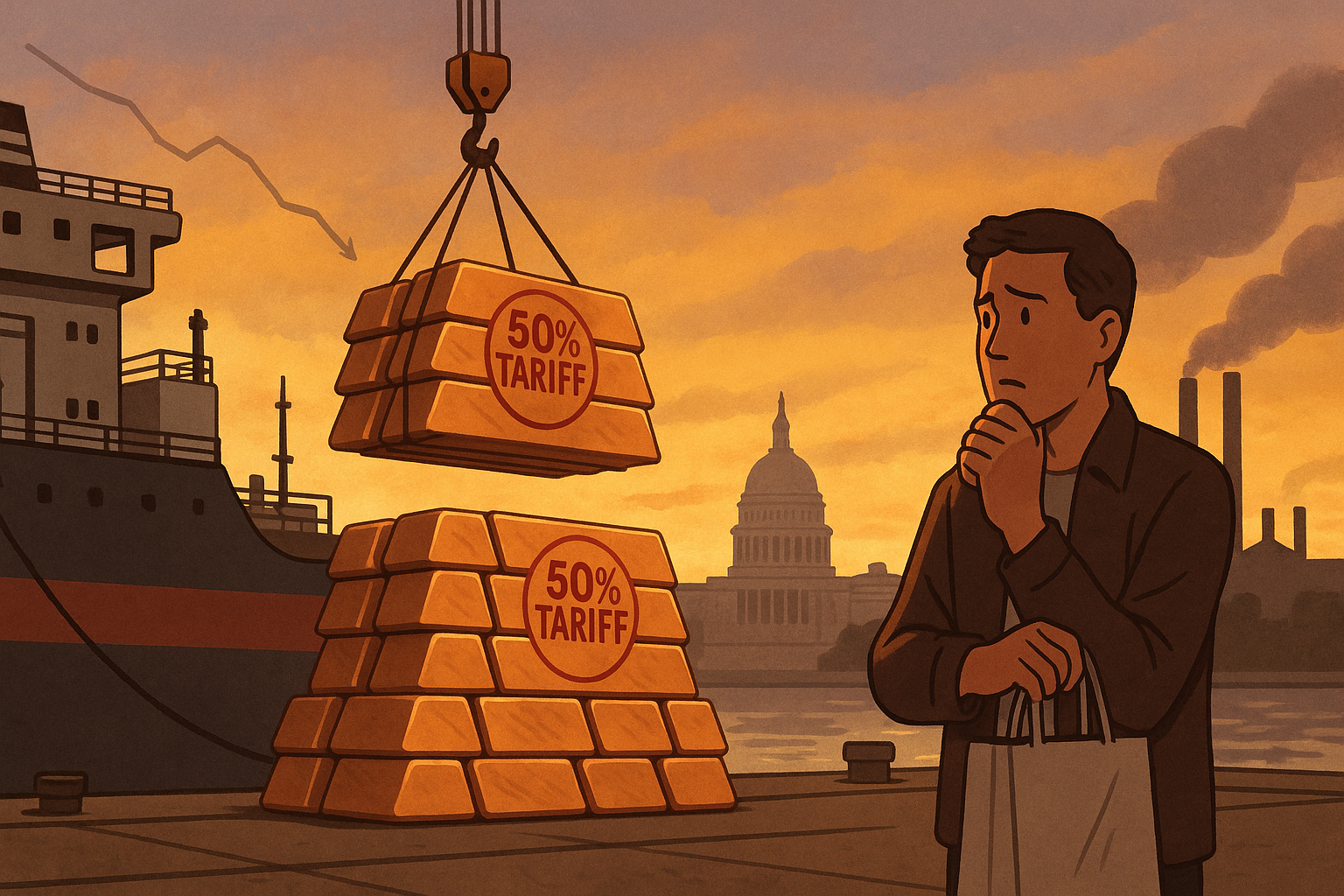

Former President Trump sent markets into a tailspin yesterday with his bombshell announcement of massive tariffs targeting—wait for it—more than 70 countries. We're talking serious numbers here: 15% to a whopping 50% on certain goods, with our neighbors to the north getting slapped with a hefty 35% penalty. Copper importers? They're looking at an eye-watering 50% tax.

The announcement represents a dramatic escalation of Trump's "America First" economic doctrine. His previous tariff battles now look like warm-up exercises.

Look, I've covered trade policy since the early NAFTA days, and there's always been a fundamental disconnect between the political messaging around tariffs and their economic reality. Politicians love to frame tariffs as penalties on foreign countries, but any economist worth their salt will tell you they function primarily as taxes on domestic consumers.

When steel tariffs hit in 2018, I watched American manufacturers struggle with higher input costs while passing the pain downstream. Their promised renaissance? Largely unrealized.

The copper tariff deserves special scrutiny. They don't call copper "Dr. Copper" for nothing—it's practically economic clairvoyance in metal form, used in everything from home construction to the iPhone in your pocket. Slapping a 50% surcharge on this critical material isn't just economically questionable... it's bizarre.

(I spoke with three manufacturing executives yesterday who were absolutely floored by this particular tariff choice.)

The protection-inflation tradeoff is something I've seen play out repeatedly in economies worldwide. The last round of Trump tariffs added roughly half a percentage point to core inflation. This new batch—broader and steeper—could easily double that impact.

And Canada? Getting hit with 35% tariffs?

That's... peculiar. Our supply chains are so intertwined that some components cross that border multiple times before becoming finished products. It's not like turning a dial; it's throwing a wrench into a finely calibrated machine that took decades to build.

The market reaction was swift, if somewhat confused. Steel producers initially rallied—then sank as investors remembered these companies use imported materials too. Retailers took an immediate hit. The Mexican peso and Canadian dollar? Both got absolutely clobbered.

There's a theory in certain economic circles that tariffs can serve as negotiating leverage. That might work with countries where trade relationships are relatively simple. But with deeply integrated economies like Canada and Mexico? It's like threatening to hold your breath until someone gives you candy. Who exactly gets hurt first?

Now, we've seen this movie before. The Smoot-Hawley tariffs of 1930 deepened the Great Depression as trading partners retaliated. While today's global economy has different resilience factors, the basic principles of trade retaliation haven't changed a bit. The EU and China are already drafting their responses—I've confirmed this with sources in Brussels who describe "contingency planning in overdrive."

The copper tariff saga is worth a deeper dive. Chile and Peru would face severe economic damage—but so would American industries dependent on copper inputs. EVs require four times the copper of conventional vehicles. Solar installations? Copper-intensive. It's almost as if... well, I won't speculate on motives.

Having covered three major trade disputes in the last decade, I can tell you that markets hate uncertainty above all else. Supply chain executives who just finished their post-COVID restructuring are now staring at their whiteboards in horror. The certain winners? Trade lawyers and consultants. Their phones are ringing off the hook.

Perhaps the greatest irony here? Tariffs presented as inflation-fighters reliably produce the opposite effect. If your concern is high prices at Walmart, adding a 20-50% tax on imported goods seems... counterintuitive.

But then again, maybe there's some 4D economic chess being played that I'm missing entirely. Wouldn't be the first time. But from where I sit, with the data in front of me and twenty years covering economic policy, it looks an awful lot like burning down your greenhouse to kill aphids.

And American consumers will be the ones feeling the heat.