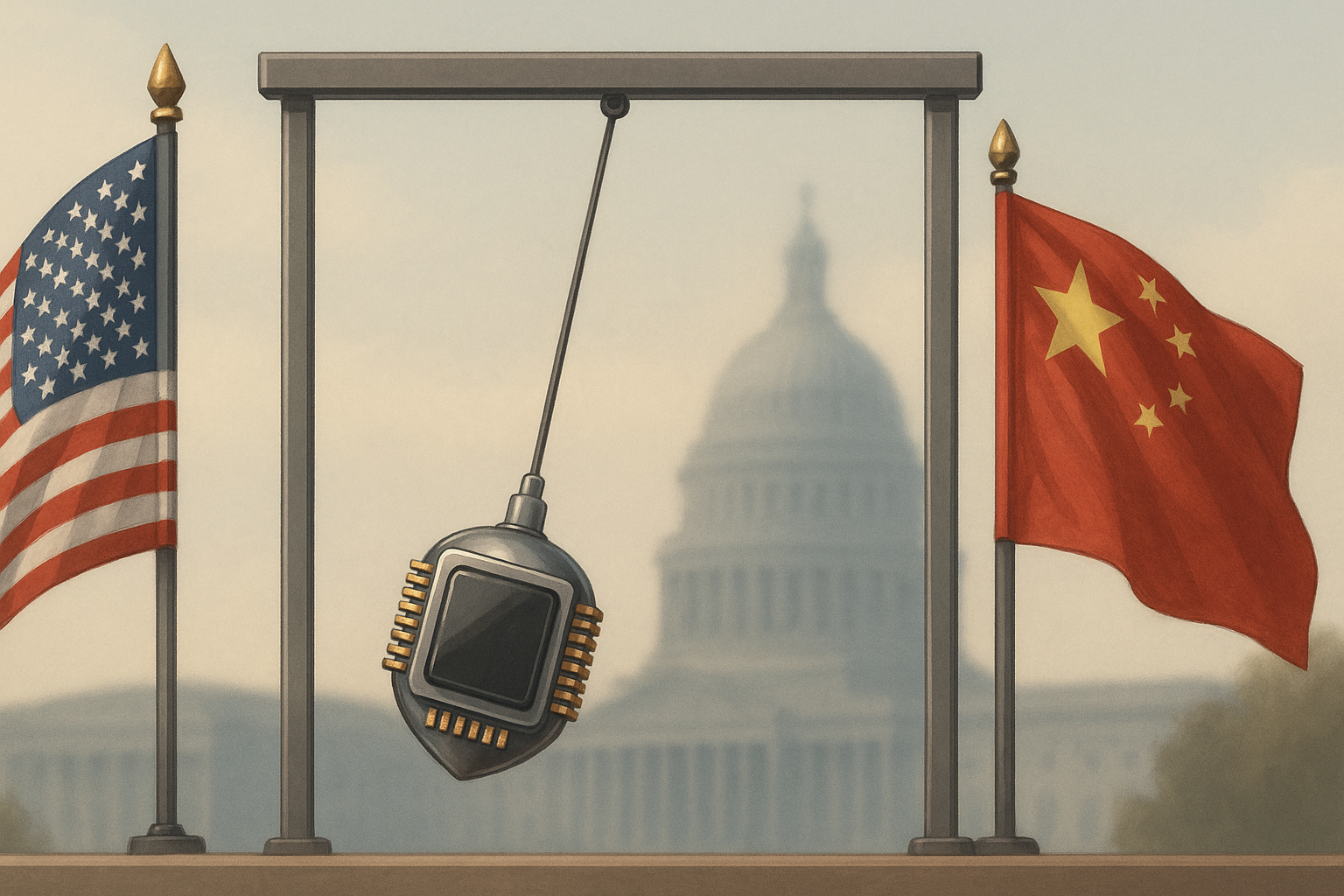

Well, this is interesting. Just when I'd gotten used to the idea that Chinese engineers were on the permanent naughty list, the U.S. has apparently decided they're welcome back at the silicon design table. Siemens, Synopsys, and Cadence—the holy trinity of chip design software—announced Thursday that the Commerce Department had essentially sent them a giant "never mind" letter, walking back export controls that had been touted as crucial to national security.

Talk about whiplash.

For almost two years now, we've heard endless warnings about the existential danger of letting China get its hands on advanced semiconductor tech. National security! Economic competitiveness! The future of the free world! Yet somehow, with minimal public debate, significant restrictions have been quietly lifted with the bureaucratic equivalent of "as you were."

I've covered tech policy long enough to recognize what's happening here. It's what I call the "security theater pendulum"—first, identify a legitimate concern, then dramatically overreact, wait for the affected companies to scream about lost revenue, and finally settle on a more measured approach that probably should have been the starting point.

The economics aren't complicated. American chip design software companies make a ton of money from Chinese customers. Cut off that revenue stream and two bad things happen: U.S. firms have less cash for R&D, and Chinese competitors get a golden opportunity to develop homegrown alternatives. The security math is trickier. How much does access to specific design tools actually accelerate China's semiconductor capabilities? Apparently, someone at Commerce has new thoughts on that calculation.

(It's worth noting that I reached out to several sources at these companies who confirmed this represents a significant policy shift, though none would speak on the record about the specific technologies now cleared for export.)

What fascinates me about these decisions is how they reflect America's schizophrenic relationship with China. The Pentagon sees a strategic competitor. Wall Street sees an essential market. Silicon Valley sees both threat and partner. And these competing visions battle it out daily inside the Beltway, producing policy that zigzags like a drunk driver on a mountain road.

Look at the broader picture: Biden kept most Trump tariffs, added new restrictions on manufacturing equipment and AI chips, but is now selectively unwinding certain controls. It's approach-retreat-approach, with no clear endgame in sight.

Investors, predictably, loved the news. Synopsys shares jumped as analysts rushed to add back hundreds of millions in expected Chinese revenue. I call this the "restriction relief rally"—when forbidden fruit suddenly becomes permissible again, stocks tend to pop as everyone recalculates future earnings.

But here's an uncomfortable truth I've learned from years covering export controls: they leak like sieves. Even during the height of restrictions, Chinese firms found creative workarounds through third countries, shell companies, and alternative supply chains. The effectiveness of any control regime depends heavily on getting allies on board, which... let's just say results have been mixed. European and Japanese companies have their own commercial interests that don't always align with Washington's security concerns.

History offers some perspective here. The COCOM restrictions during the Cold War did slow Soviet tech advancement in some areas, but couldn't stop the eventual spread of key technologies. And that was in a far less interconnected world! Today, with global supply chains and instant information flows, containing technology is like trying to hold water in a net.

For companies in the semiconductor world, this regulatory yo-yoing creates both headaches and opportunities. The firms that can navigate the shifting political winds—maintaining Chinese market access while staying in Washington's good graces—will outperform. Others might find themselves making expensive global adjustments only to reverse course months later when the policy winds shift again.

So does this relaxation signal a broader reset in U.S.-China tech relations? I doubt it. The fundamental strategic competition remains; we're just seeing tactical adjustments in how it plays out through specific policies.

After all, semiconductor development, like geopolitics, proceeds in iterations. Design, test, debug, release new version. Washington seems to be on its own semiconductor policy revision cycle—though with quality control standards that would make any decent chip engineer cringe.