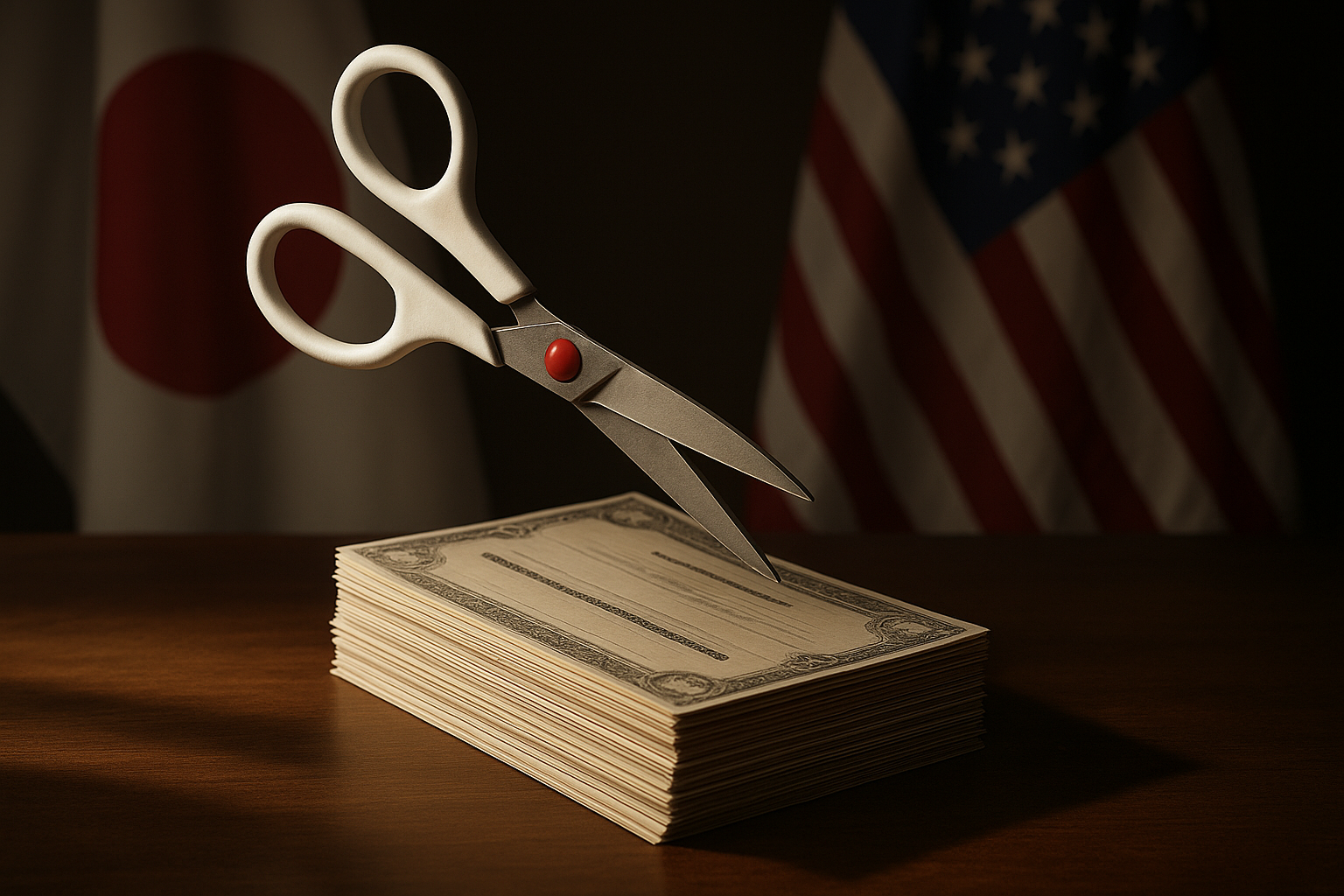

Japan just tossed a financial hand grenade into the global conversation—pin pulled, but not quite thrown. In what might be the understatement of the year, Japanese Finance Minister Katsunobu Kato casually mentioned that the country's massive $1.13 trillion U.S. Treasury holdings could be a "card on the table" in ongoing trade discussions with America.

Let's be crystal clear about what this means. We're not talking about minor diplomatic posturing here. This is Japan—America's largest foreign creditor—suggesting it might dump U.S. debt as a bargaining chip. It's like your mortgage holder casually mentioning they might call in your loan... while you're arguing about the property line.

I've been covering international finance for years, and these kinds of threats typically remain unspoken. There's an unwritten rule in global finance: you don't explicitly threaten to use debt holdings as weapons. Yet here we are.

The timing isn't accidental. This comes directly in response to renewed tariff saber-rattling from Washington. Tokyo's message couldn't be clearer: "You want to play hardball with tariffs? We've got a trillion reasons for you to reconsider."

But here's where it gets complicated—and why I doubt Japan would actually follow through. Any significant Treasury selling would create a financial murder-suicide pact. Japan would hurt America by driving up interest rates, sure, but they'd simultaneously:

- Take massive losses on their remaining Treasury portfolio

- Potentially strengthen the yen (devastating for Japanese exporters)

- Face the impossible question: where exactly do you park a trillion dollars instead?

It's financial mutually assured destruction. (And yes, the Cold War metaphors are entirely appropriate here.)

Markets understand this dynamic, which explains why we haven't seen panic selling... yet. The Japanese know that merely suggesting they might sell can apply pressure without actually having to dump bonds. Show the gun, don't fire it.

We've seen this movie before, haven't we? China occasionally hinted at the "nuclear option" during previous trade tiffs, but never pulled the trigger. The self-harm would be too great, and frankly, there simply isn't another market deep enough to absorb that kind of money. Where else offers both the liquidity and safety of U.S. Treasuries?

Look, what's truly concerning here isn't just this specific threat—it's what it represents. Financial markets increasingly function as battlegrounds for geopolitical conflicts. Treasury holdings, currency reserves, payment systems... these aren't just financial assets anymore; they're weapons in diplomatic arsenals.

For American investors (and I've spoken with several this week who are legitimately concerned), this adds layers of complexity that weren't in the old playbooks. Treasury yields now reflect not just inflation expectations and growth forecasts, but also the probability of foreign financial warfare. Good luck pricing that risk on your spreadsheet.

In the meantime, I'll be watching the monthly Treasury International Capital data like a hawk. Sometimes the real moves happen in the shadows while the threats play out in public.

My hunch? This particular threat remains just that—a threat. The financial equivalent of a strongly worded letter. But it's a stark reminder that in our interconnected system, economic strength and vulnerability are often flip sides of the same coin. The privilege of printing the world's reserve currency comes with strings attached.

And those strings? They can be pulled at the most inconvenient times.