Major car manufacturers are nursing billion-dollar headaches these days. The latest financial reports reveal an eye-watering $11.7 billion hit to the automotive industry in the first quarter alone—all thanks to the Trump administration's expanding tariff policy.

Toyota seems to be taking it on the chin hardest, with a $3 billion loss. General Motors is scrambling to relocate about $4 billion worth of production back to American soil. Even Tesla—yes, the same company whose CEO has been cozying up to the administration—is feeling a $300 million sting.

I've been covering trade disputes since before most people could spell "globalization," and there's something fundamentally different this time around. This doesn't have the feel of your typical negotiating posture. No, this looks more like a forced restructuring of automotive supply chains that took decades to optimize.

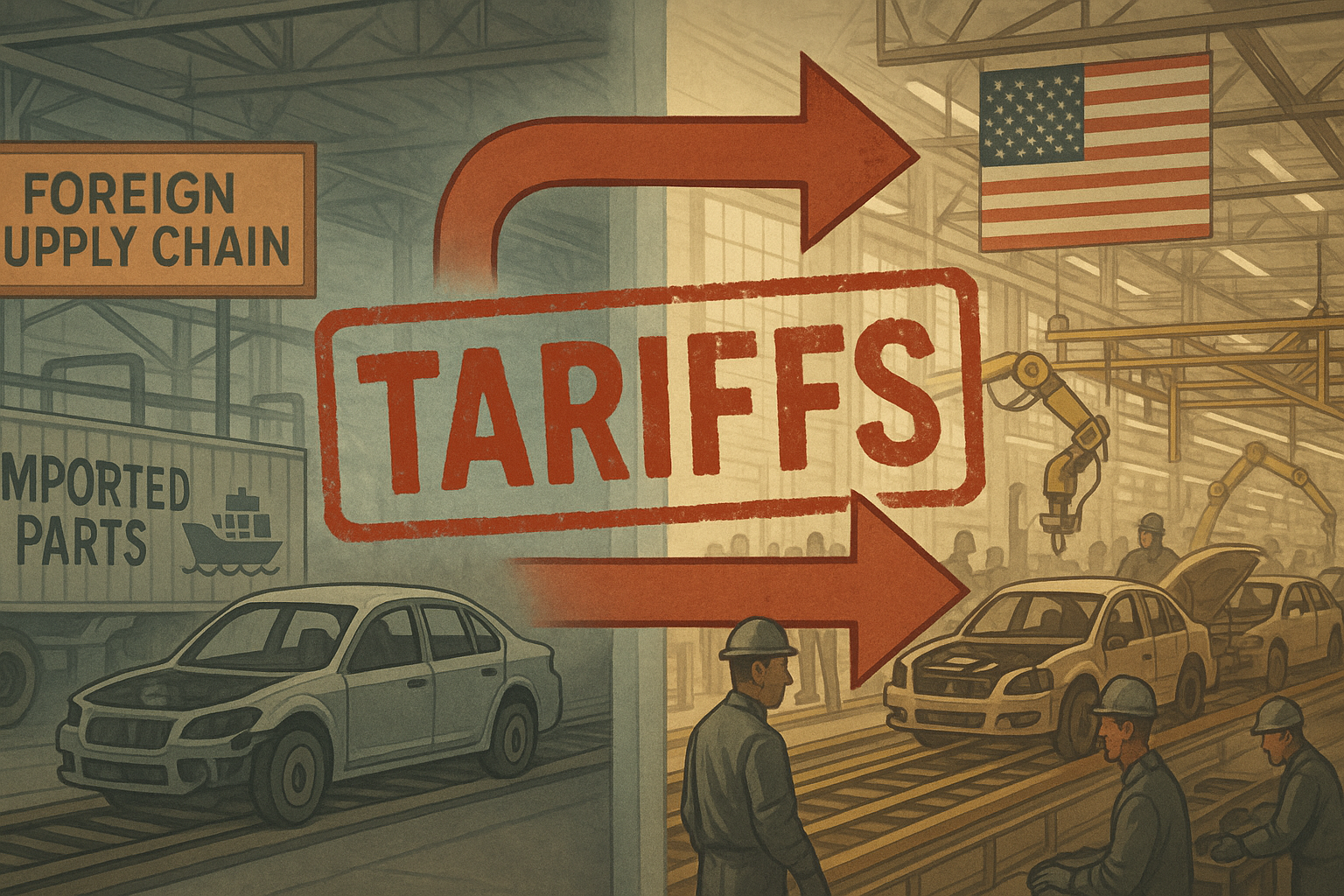

When tariffs first hit an industry, there's a predictable pattern. Companies initially absorb the costs, hoping the whole thing blows over quickly. When it doesn't, they reluctantly pass those costs to consumers. And when it starts looking permanent? That's when they tear up their operations and start rebuilding.

We're now in that third phase, folks.

The Toyota situation strikes me as particularly ironic. Here's a "foreign" company that's been building cars in Kentucky for decades, employing thousands of Americans, getting hit harder than some "American" brands whose parts come from a dozen different countries. Makes you wonder what we're really protecting, doesn't it?

GM's decision to shift $4 billion in production back to the U.S. is exactly what these tariffs were designed to accomplish. CEO Mary Barra has essentially thrown up her hands and said, "Fine, we'll bring it home." But nobody's talking about the invisible costs here—reduced efficiency, higher production costs, less flexible supply chains. These won't show up neatly on a quarterly statement, but trust me, they're real.

Look, there was a reason these operations went global in the first place. And it wasn't just because auto executives enjoyed hotel points in Shanghai.

(Speaking of ironies, how about Tesla? Elon Musk has been one of the administration's most vocal supporters in the business world, yet his company is taking a $300 million hit from the very policies he's championed. That's gotta sting during the quarterly board meetings.)

The market analysts, predictably, are focused on immediate quarterly damage. They're missing the forest for the trees. This isn't just about Q1 numbers or even 2023 projections. We're watching the forced reconfiguration of roughly 10% of the American economy.

What happens to those towns in Mexico and China that built their economies around auto parts manufacturing? What about American consumers who'll ultimately foot the bill for these changes? And how will U.S. automakers compete globally when their cost structures are artificially inflated?

I had coffee last week with a supply chain executive at one of the Big Three who told me, on condition of anonymity, "We're basically ripping up 30 years of optimization work and starting over. It's like telling a surgeon halfway through an operation to use different instruments."

The conventional wisdom suggests these tariffs will eventually lead to some grand negotiated settlement. I'm skeptical. This feels more like a permanent shift in how global trade functions—less free, more managed, more political.

For investors, the automotive sector now carries a triple threat: cyclical risk, technological disruption risk, and heightened political risk. Valuing these companies means not just analyzing consumer demand and production efficiency, but also predicting which way the political winds will blow.

And isn't that just what we all wanted from our car companies? To become political footballs rather than, you know, efficient producers of reliable transportation?

The road ahead looks bumpy. Hold on to your steering wheels.